The Reader and the Sleeping Stars

Continuation of The Sphere and the Moon. The Scribe of the Stars: The Vatican Library Read Chapter 1 first.

Chapter 2 — The Reader and the Sleeping Stars

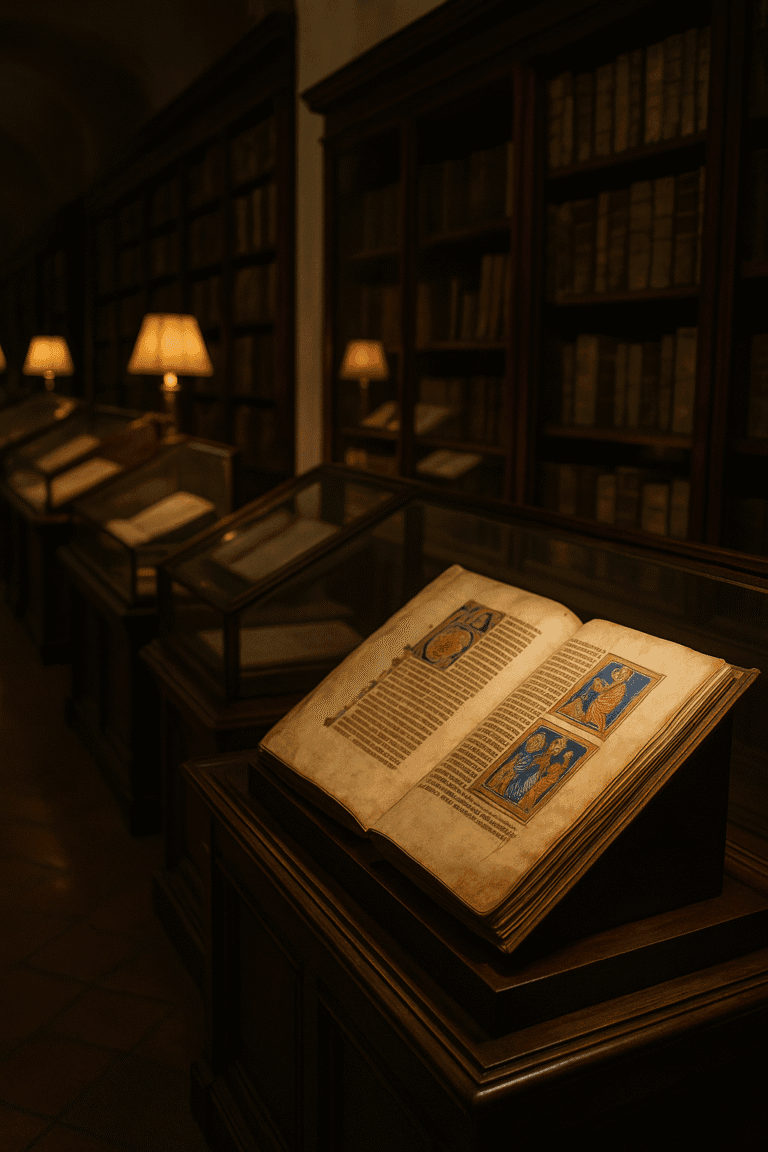

The room is filled with scholars eager to uncover enigmas, decipher codes, and decipher memories. The glass-covered shelves are filled with volumes of every color and seem to support not only the room's ceiling, but the entire firmament.

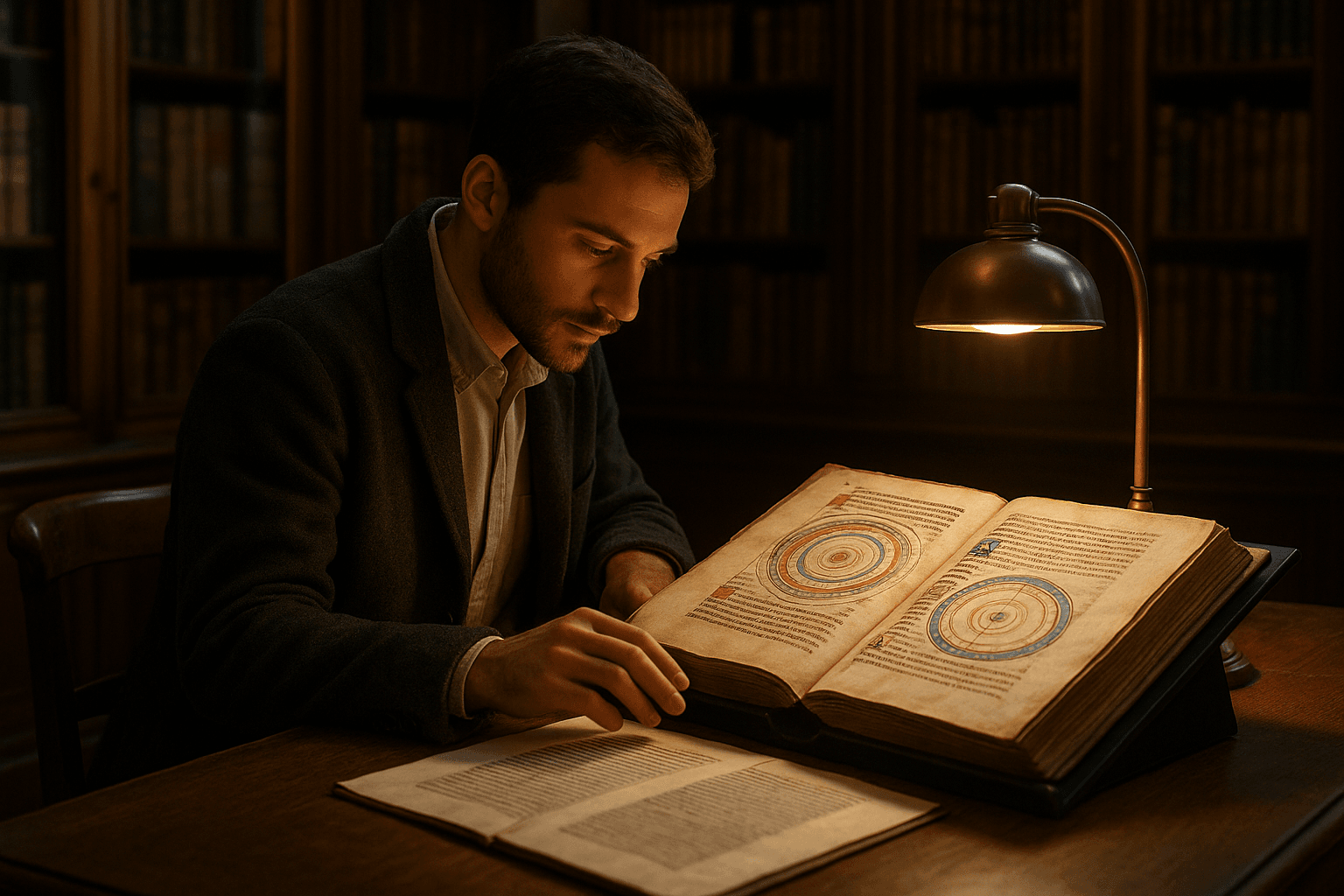

Our student—a doctoral candidate with a trembling gaze—walks briskly. He doesn't want to break the silence that smells of parchment, noble dust, and lamps extinguished for centuries. He places the codex on the table, under the golden light of a lamp that awaits him like a patient sun. The pages open like wings.

Suddenly, he's no longer alone: each manuscript around him is a planet; each display case, an orbit. He looks up and discovers a constellation of titles:

- From Sphaera Mundi — Johannes de Sacrobosco (13th century)

The book that for four centuries explained the cosmos in perfect circles. Diagrams of spheres, commentaries in red and black. The universe like a precise clock, even if time later corrected it. - Alphonsian Tables (translations from Arabic, 13th-14th centuries)

There, the arithmetic of the stars: planetary positions, calculations of the sky inherited from Toledo and deployed throughout Europe. The voices of Arab astronomers throb in their numbers. - Codex Palatinus 1414 — a mosaic of knowledge (14th century)

Together in the same volume: Zarqālī, Messahalla, Gerard of Cremona. A cultural palimpsest where East and West joined hands under the same sky. - Medieval volvellas — movable paper discs (15th century)

Cut-out and superimposed wheels that, when turned, reveal lunar phases and planetary trajectories. A portable astronomy: paper clocks that turned like grave toys in the hands of scholars. - Hebrew translations of the De Sphaera (Vat. ebr. 292, 382)

The same text in a different alphabet: curves and crowns, letters that seem to dance with celestial physics. Science traveling from language to language like a persistent comet.

The doctoral student scans each illuminated initial with his eyes. The letters aren't just words: they're celestial bodies, with enough gravity to attract centuries of questions. He runs a finger—without touching, just following the outline in the air—over a circular diagram.

Think: Here, an anonymous man under a clear moon drew lines. Now those lines are my compass.

He shudders. He realizes that reading is like conversing with a stranger across seven centuries.

The lamp flickers. Outside, Rome breathes. Inside, the library guards its greatest secret: the certainty that human thought can folding the centuries, bringing past and present closer together like someone folding a sheet of parchment.