The Sphere and the Moon

The Star Scribe

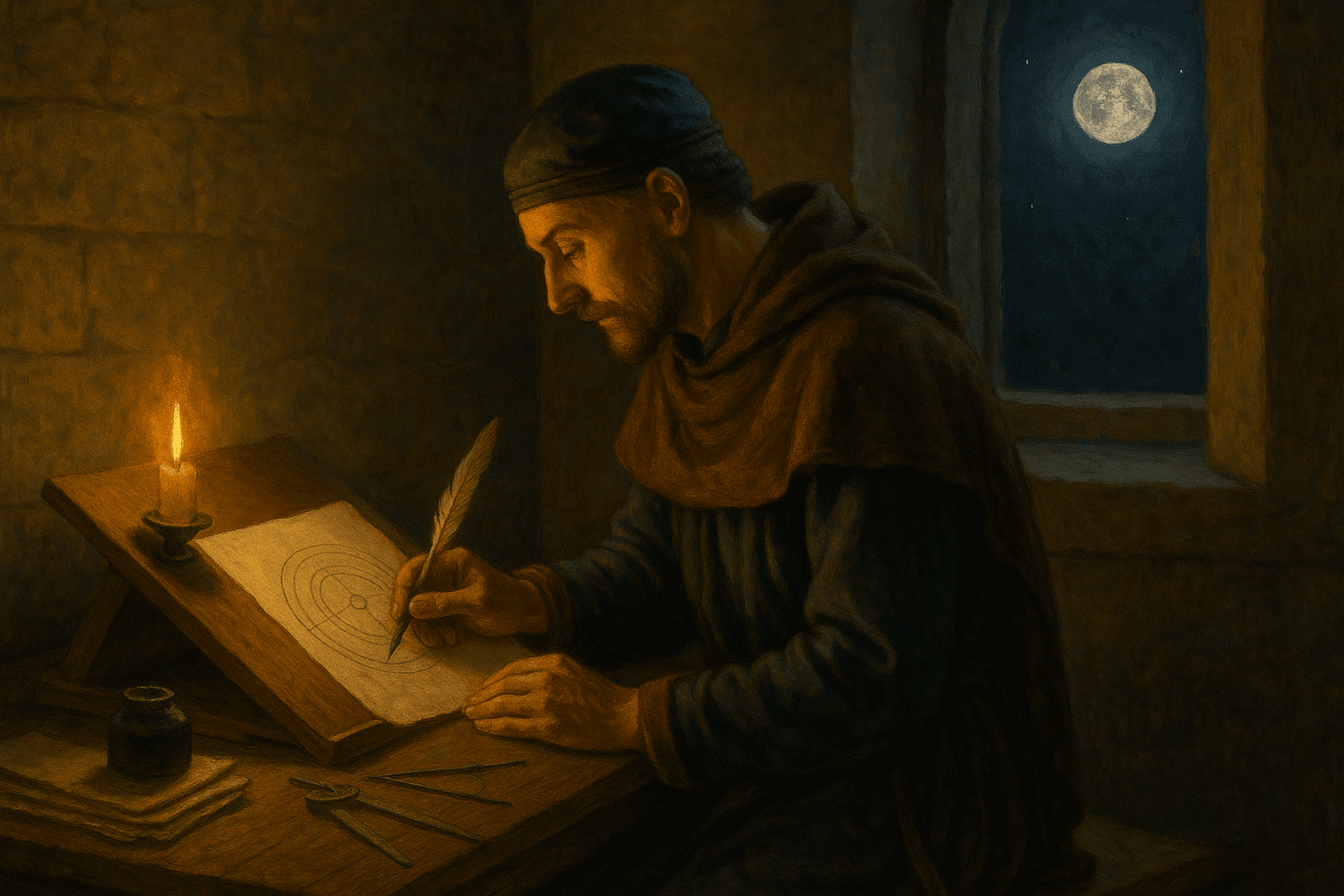

It was a full moon night. The light reflected off the rooftops, almost as if the night had embroidered them with threads of light.

He—we won't reveal his name; good copyists prefer anonymity—would gaze at the stars until he was lost, and when he came to, the moon would rest on the edge of the inkwell like a patient lamp.

He laid down his pen. The first stroke was inspired: a curve, then the technique, the first straight line, a perfect 90 degrees. Between the two, the slightest tremor of a dot.

Thus the text began to take life, characters like constellations: antlers that rise, bellies that roll, pinpoint eyes that mark accents; a choreography of black lines against the clear silence of the parchment.

He drew a circle with his compass, and within it another and another: the music of the spheres translated into geometry. In the margins, the key words were highlighted in red; in blue, the initials that breathed the ocean.

He noted: De sphaera mundiHe didn't invent the universe; he refined it, sculpting it like a master marble. Each letter advanced at the pace the stars set when no one is looking: slow, precise, inevitable.

At times, the scribe would look up, and the moon seemed to nod. He would return to the paper and trace small figures: a circle for the Earth, bands for the heavens, a diagram like a clock without hours.

If any doubt arose, he resolved it with the patience of a craftsman: repeating the letter, adjusting the line, taking a deep breath. When he added a tiny miniature—an eight-pointed star—he smiled: sometimes beauty lies in the margin.

At the end of the night, he held the sheet up to the light. It wasn't just ink, it was a way of thinking; it was days of work inspired by the moon and its skies.

And then it happened: the air changed temperature, time slipped past like a curtain, and the folio—later sewn with others into a codex—traversed centuries. It crossed hands and borders, wove libraries.

We imagine it for a moment rolled up—because imagination shows it to us that way, rolled up, suspended in libraries in the shape of diamonds of wood—but history wanted it bound, with fine threads on the spine and a signature that says: I belong here.

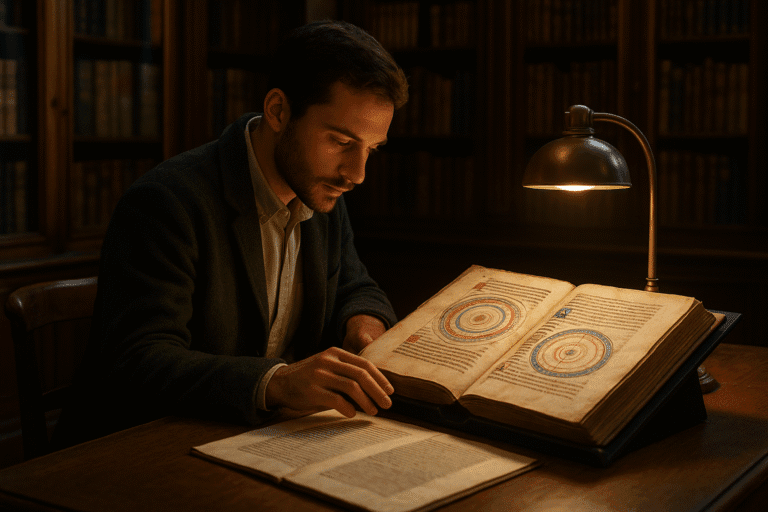

Now, in a tall, sober room, a student from the present—a doctoral candidate, precise fingers, low voice—asks for the volume. It is handed to him with an almost imperceptible nod. He opens it. The moon is no longer in the inkwell, but something of that night returns: the writer's pulse beats between the lines.

Read slowly. Recognize the circles, the marginal notes, the patience. Think of all the other books that fit on these shelves: treatises that converse with Arab astronomers, glosses that dialogue with medieval masters, commentaries that pushed the sky a millimeter further.

He closes his eyes for a moment. He doesn't pray, he gives thanks. Because in this library, wonder doesn't thunder, it whispers. And the whisper comes from a very ancient goose quill that, under a very clear moon, understood that writing is ordering stars.

Historical notes

De sphaera mundi (Johannes de Sacrobosco, c. 1230) was the most influential astronomy manual in pre-Copernican Europe.

The Vatican Apostolic Library houses several manuscripts and compilations containing the text and commentaries: Pal.lat.1400 includes Algorismus, De sphaera and From computing; Latin word 1385 brings commentators such as Albertus de Brudzewo; Reg.lat.1013 contains the From quadrant; Vat.lat.3110 It contains an astronomical miscellany with extracts; and there are Hebrew versions of the De sphaera in Vat. ebr. 292 and Vat. ebr. 382.

The Vatican also keeps astronomical-astrological compilations where Latin authors and the scientific-Arabic tradition coexist (e.g., Arzachel/Zarqālī, Messahalla, Gerard of Cremona), as in Latin word 1414.

Chapter 2 — The Reader and the Sleeping Stars

The room is filled with scholars eager to uncover enigmas, decipher codes, and decipher memories. The glass-covered shelves are filled with volumes of every color and seem to support not only the room's ceiling, but the entire firmament.

Our student—a doctoral candidate with a trembling gaze—walks briskly. He doesn't want to break the silence that smells of parchment, noble dust, and lamps extinguished for centuries. He places the codex on the table, under the golden light of a lamp that awaits him like a patient sun. The pages open like wings.

Suddenly, he's no longer alone: each manuscript around him is a planet; each display case, an orbit. He looks up and discovers a constellation of titles:

- From Sphaera Mundi — Johannes de Sacrobosco (13th century)

The book that for four centuries explained the cosmos in perfect circles. Diagrams of spheres, commentaries in red and black. The universe like a precise clock, even if time later corrected it. - Alphonsian Tables (translations from Arabic, 13th-14th centuries)

There, the arithmetic of the stars: planetary positions, calculations of the sky inherited from Toledo and deployed throughout Europe. The voices of Arab astronomers throb in their numbers. - Codex Palatinus 1414 — a mosaic of knowledge (14th century)

Together in the same volume: Zarqālī, Messahalla, Gerard of Cremona. A cultural palimpsest where East and West joined hands under the same sky. - Medieval volvellas — movable paper discs (15th century)

Cut-out and superimposed wheels that, when turned, reveal lunar phases and planetary trajectories. A portable astronomy: paper clocks that turned like grave toys in the hands of scholars. - Hebrew translations of the De Sphaera (Vat. ebr. 292, 382)

The same text in a different alphabet: curves and crowns, letters that seem to dance with celestial physics. Science traveling from language to language like a persistent comet.

The doctoral student scans each illuminated initial with his eyes. The letters aren't just words: they're celestial bodies, with enough gravity to attract centuries of questions. He runs a finger—without touching, just following the outline in the air—over a circular diagram.

Think: Here, an anonymous man under a clear moon drew lines. Now those lines are my compass.

He shudders. He realizes that reading is like conversing with a stranger across seven centuries.

The lamp flickers. Outside, Rome breathes. Inside, the library guards its greatest secret: the certainty that human thought can folding the centuries, bringing past and present closer together like someone folding a sheet of parchment.